Inheriting an Identity in "Snapshots: this Afghan American life"

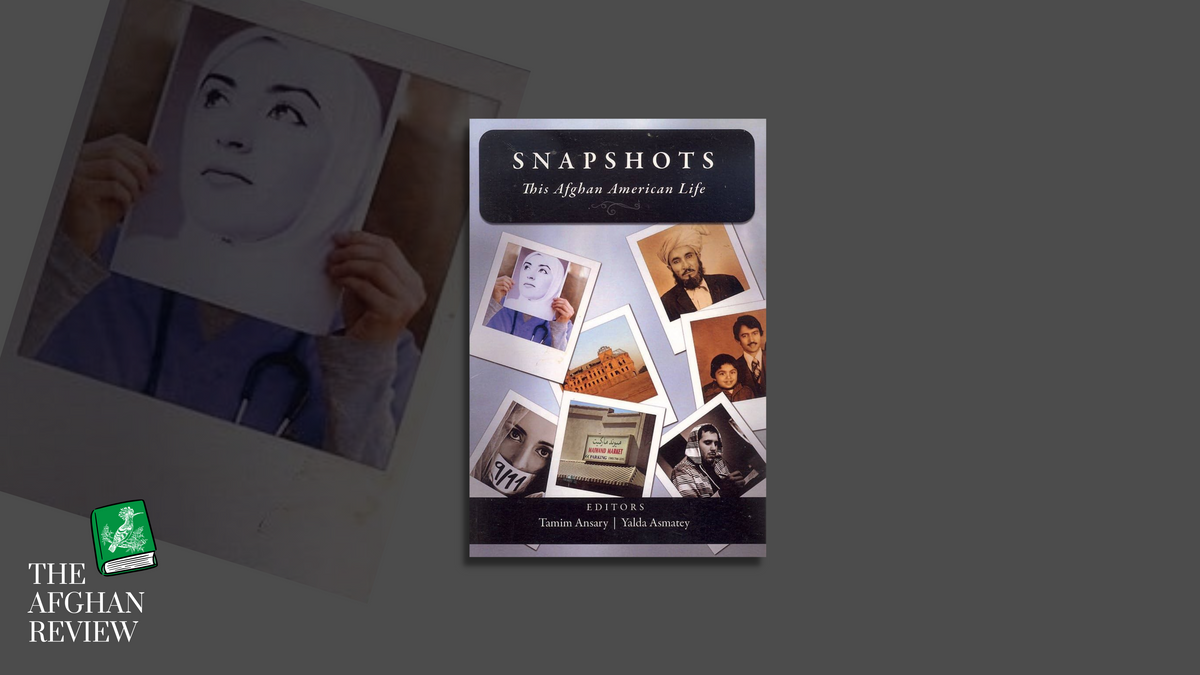

We are all born with an inheritance. It can be material—money, a house—or immaterial—a people, a culture, a feeling. At its most helpful, an inheritance can launch us towards our most ludicrous dreams. At its most common, it can trap us into a circuitous life of received habits, devoid of agency. In all circumstances, it’s difficult to know what to do with an inheritance, but it is our obligation to decide. In Snapshots: this Afghan American life, 15 emerging writers inherit an Afghan identity while living in the U.S., a place where they have little room or guidance to reckon with it. Each writers’ unique struggles lead them on a path to acceptance as they come to terms with their heritage, their circumstances, and, eventually, themselves. Published in 2008 by editors Tamim Ansary and Yalda Asmatey, Snapshots is a remarkable nonfiction anthology that paves the way for an Afghan American voice in literature that is compassionate, forgiving, and expansive.

In his introduction, editor Tamim Ansary’s identifies a foundational difficulty in the emergence of an Afghan American voice: “Growing up in the shadow of their parents’ epic dramas, the horrors generated by the all-but-total destruction of their country in the late twentieth century, this first generation of Afghan-Americans has a story of its own to tell, a subtler one perhaps, but just as gripping.” Yet these stories don’t always feel subtler than those of Afghans coming out of Afghanistan. In “Hope Street,” Bismillah writes about physical abuse, drug dealing, and poverty in a raw, confident voice that reminds us that when people travel across borders, their problems don’t disappear. While they may not be direct translations of the problems they would have had in their homelands, they are analogous. Bismillah’s circumstances, his adversity and pain, are not uncommon, yet they remain untold in the Afghan American context, which makes this telling that much more necessary.

Snapshots contains a lot of stories about parents. It makes sense considering that parents are often the strongest access point to an Afghan heritage for an Afghan American child. Misunderstanding trails these parental characters rendering them vulnerable to judgement from their children and from outsiders, non-Afghans. In response to this consistent misunderstanding, Amina Zamani, Waheeda Samady, and Hosai Mojaddidi write to the theme of the deceptiveness of appearance. “Pink Plastic Curlers,” is a sweet, youthful story in which Zamani learns to make sense of what she initially understood as her mother’s inappropriate protectiveness. In Samady’s story, “The Cab Driver’s Daughter,” her father is the main character. She tells of how he loses his occupation and thereby his social status in the move to the U.S., and how it all affects her. Though heavily didactic, Samady’s strong depiction of the bond between her and her father gives credence to her message that we should look past accents and other markers of foreignness and see people for who they have worked hard to become. Sacrifice also informs many depictions of parents in the anthology. Mojaddidi highlights her father’s sacrifices in her description of him in “A Place of Our Own,” a story about opening an Afghan grocery store: “As a young man, he had studied English abroad, but he still had a heavy accent which seemed to deter employers from hiring him. So he decided to set all of his personal ambitions aside and work solely to survive and to provide for us.” Through their parents and the sacrifices they make for their children, the writers of the anthology communicate so much of who they themselves are and what they value.

Along with these heavy themes, there are lighter moments filled with humor. At times, the book made me laugh out loud. This happened with “Afghans Kissing” by Asiyah Sarwari, a story in which she sends an email to apologize for kissing an elder on the cheek. Sarwari humorously fumbles through Afghan cultural norms, giving it her best effort: “There would be elders who wanted their hand kissed, elders who didn’t want their hand kissed. Elders who did want their hand kissed but had to pretend like they didn’t and so you didn’t and they never really liked you as a result.” Then there’s Reza Sayeed describing his clothing mishaps in “A Tough Shell:” “I came to the US when I was 3, but not until 6th grade did I begin to feel like an immigrant…The others started wearing surf t shirts while my mom still dressed me up like an elderly British man.” The stories are funny because they are deeply relatable—as in, I have been there, and I’m sure many other first-generation Americans have too—but also, because they are surprising. Representations of Afghan Americans are still so rare that surprise feels like it’s always at hand, and therefore humour might be too.

“A Tough Shell,” began as one of my favorite stories in the anthology, but it ended as one of the most problematic. It starts by highlighting the pressure immigrant boys feel to respond to discrimination with hyper masculinity and aggression. Sayeed is doing important work by discussing such a widespread yet untold experience, but his proposed solution to the problem tarnishes the entire piece. His story ends with an anti-Black polemic glorifying tradition. Sayeed identifies rap music and its “aggression” as the “worst of the United States,” and encourages Afghan Americans to reject Black culture in order to return to cultural practices inherited from Afghanistan. Rap music and Black culture are still often portrayed and valued negatively in Afghan communities (and America at large), but Black culture and its overt resistance is often the only part of America that poor immigrant kids feel a connection to. Many identities and cultures in the United States draw from the confidence and assertiveness in Black culture to create their own forms of communal self-expression. (Which minority rights movement doesn’t stem from Black radical movements?) To think that an Afghan American identity can form without the influence of Black America is dishonest. Sayeed also criticizes immigrants who speak neither their mother tongue nor English “correctly,” which sets up another impossible expectation for Afghan Americans. The goal posts of linguistic authenticity are always changing as new dialects are formed and identified by linguists. (An example is the recent identification of the Only in Dade dialect in southern Florida). While Sayeed’s solution is not helpful, his essay does important work by identifying hypermasculinity as a pressing problem in our community—one that can be isolating and lead to feelings of inferiority and lifelong suffering for Afghan men and boys. (He also reveals anti-Blackness as a pressing problem in our community, which is also important though less intentional.) I suspect that if he were to revisit this piece, Sayeed may himself agree that while holding on to tradition can be an important source of self-esteem, allowing newness and change into our lives is too. After all, American culture is supposedly formed on a bedrock of cultural and linguistic innovation that blurs the borders between traditions.

Overall, the book is a delightful and important read. As emerging writers, their stories can be difficult to follow and their larger themes difficult to identify, or they can be overstated, but the book contains a rare rawness that we so often only get from debut authors. Published 15 years ago, the stories contend with issues that Afghan Americans still face today, and will continue to for the foreseeable future, given that the influx of Afghan refugees to the United States has steadily increased over continued decades of political instability in Afghanistan. In “A Place of Our Own,” Hosai Mojaddidi’s family opens an Afghan grocery store that eventually closes only a year after opening. It’s a story about actively creating belonging and trying hard to accomplish something no matter the outcome. We Afghans often try hardest at hiding our perceived failures. Here is a story of trying and being proud of just doing that, regardless of failure. Similarly, this anthology is an excellent effort to draw Afghan American stories into the fold of American literature. And in that effort alone, trying to carve out a new identity and literary voice out of an old heritage, it is wonderfully successful.

Rating: ★★★

SNAPSHOTS: this Afghan American life | Edited by Tamim Ansary and Yalda Asmatey | 89 pp. | Kajakai Press