Afghan Womanhood as Transnational in "Dear Zari"

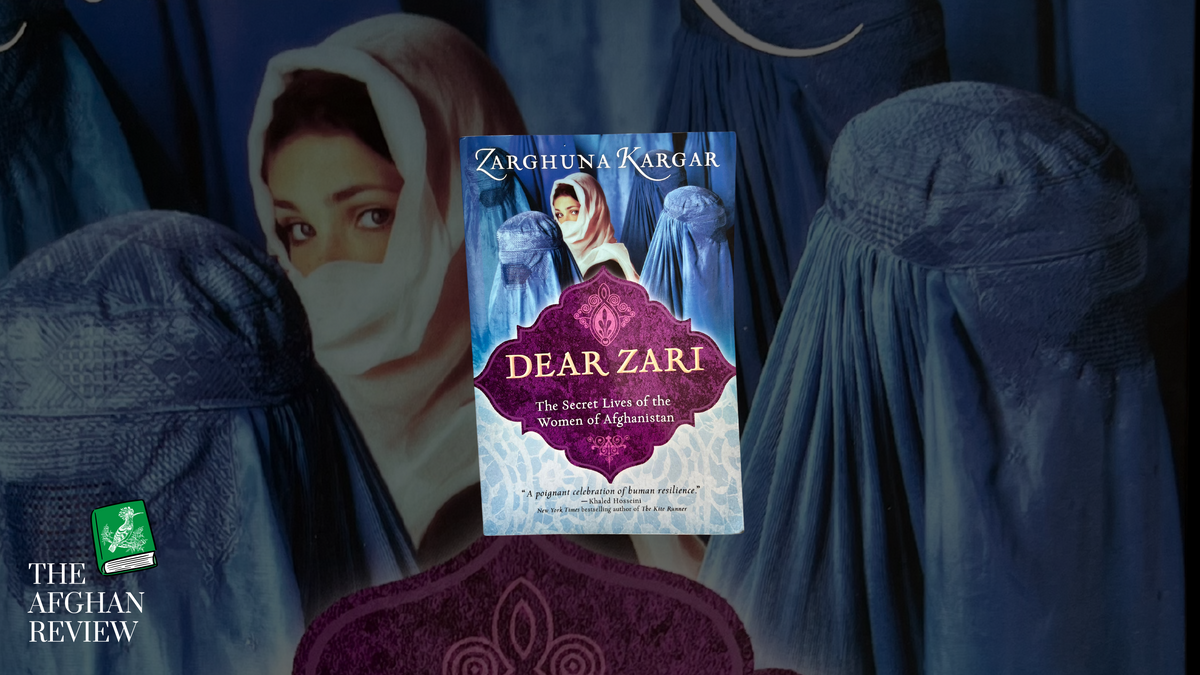

Despite a sensational cover image and Desperate Housewives-esque subtitle, Zarghuna Kargar’s book Dear Zari: The Secret Lives of the Women of Afghanistan is as much for Afghan women as it is about them.

Compiled during Kargar’s time producing the BBC radio show Afghan Woman’s Hour, the stories in this memoir anthology track the lives of Afghan women as they gain and—overwhelmingly—lose power. There are stories of rich women, poor women, abused women, loved women, powerful and powerless women—and none of these categories are mutually exclusive.

There have been numerous attempts to compile Afghan women’s stories to share with English readers. Projects often fall victim to tropes and stereotypes that flatten Afghan womanhood into helplessness and utter boredom. But Dear Zari does the opposite. By focusing heavily on individual experiences—realistic, relatable, and intimately wrought experiences—it manages to subvert expectations of reductionism.

Published in 2011, the book covers a wide range of Afghan women’s issues that circumambulate one haunting assumption: it is more valuable—socially, economically, and, to some, morally—for a family to have a son than a daughter. This feeds into the harmful, self-propagating assumption governing gender in Afghanistan that boys and men have more value than girls and women. From this starting point, the book traces gender inequalities in its exceptional stories from individual women across Afghanistan.

Kargar begins by contextualizing Afghanistan in the prologue with a political overview. She provides a summary of the country’s political landscape from the 1970s to the 1990s, which suggests an intended audience of non-Afghans who either know little about Afghanistan or have misconceptions about the country and its political history. Then comes Kargar’s memoir followed by the memoirs of other women.

Kargar uses her authorial, and authoritative, position to bolster the other women’s stories with relevant content from her personal life. She frames each memoir with opening context and closing analysis that she—as a Pashtun woman who grew up in Afghanistan and speaks Dari, Pashto, and English—is uniquely positioned to provide. In abutting each story with her own vulnerabilities—her fears and desires as they relate to her changing nation, her family’s approval, and her romantic life—Kargar maintains the humanity of her subjects. In this way, Kargar succeeds where many other editors and writers on Afghan women have failed.

Kargar succeeds where many other editors and writers on Afghan women have failed.

Most, if not all, of the topics covered in the book are still taboo to broach in Afghan communities globally. Issues covered in the book include women’s inheritance and custody rights, the rarity of love marriages, and the suppression of LGBTQ+ identities and relationships. The book also covers more buoyant topics like women’s financial independence, successful love marriages, and the diversity of ethnicities, languages, and lifestyles in Afghanistan.

Yet, whether or not we talk about them, or are even aware of them, Kargar shows that these underlying, systemic issues continue to inform Afghans’ day-to-day lives. The message is communicated especially well through anecdotes from her married life. In one example, Kargar regularly feigns sleep in her apartment in the UK to avoid talking to her husband. This coping habit presents in alarmingly high numbers of unhappily married Afghan women around the world. Research on Afghan women’s issues is inadequate and cannot prove the existence of these high numbers, but Afghan women can; they have the qualitative data in personal experiences like Kargar’s.

One of the sweetest moments of the book was when Mahgul described the emotional intimacy between her and her husband, a man she had been wed to through an arranged marriage: “He became my friend, my soul mate, my everything. On occasions he was even like a sister to me, and we would gossip together.” Happy marriages are rare and precious—within Afghanistan and beyond.

Initially Kargar’s context is helpful, but it becomes less so at the end of the book. Following her first political overview in the prologue, Kargar doesn’t return to direct political commentary until the epilogue, where she describes Afghanistan at the time of the book’s publishing (2011) and looks apprehensively to the future. The two moments, separated by hundreds of pages, are lopsided; Kargar is disproportionately more thorough in her commentary of the 1970s to 19990s than the 2010s. In the former period, Kargar gives a lot of space to the international influence on the internal politics of Afghanistan. That international influence is almost completely absent in the short, one-page commentary on 2011 Afghanistan. In closing the book so, Kargar retreats to an insular representation of the country that reinstates Afghanistan’s position at the margins of global politics.

Kargar’s fixation on culture also tempers the books insights. She continuously attributes gendered violence and women’s oppression to a monolithic “Afghan culture.” It plays into a longstanding, false dichotomy that implies Afghan women can either be Afghan or be free, self-actualized people. She also uses reductionist terms like “civilized” when referring to non-Afghan cultures, which reinforces stereotypes of Afghans as unmodern, uncivilized people. A lot of the nuance between different ethnic groups is also lost when Kargar writes about culture in a monolithic way. An example of this is the controversial burqa, the origins of which Kargar does not attribute to a specific ethnic group, suggesting instead that it was a country-wide practice.

Similarly, Kargar’s overemphasis of culture in discussions of gender inequities minimizes a global problem into a local one. Afghans may have innumerable ways that we enact our own, unique forms of sexism, and though these manifestations sexism and misogyny may seem regionally- or Afghan-specific, the underlying thinking that plagues the nation is not local. Should even the overvaluing of boys at the expense of girls be localized to Afghanistan? Is Afghan culture the problem or global sexism?

Even so, everyone should read this book, especially English-speakers with Afghan heritage who were raised outside of Afghanistan. Afghan womanhood is transnational and affects Afghans regardless of where we are born or raised. In Gulalai’s story it is worded thus: “no matter where an Afghan woman lives, Afghan society and its culture will always treat her in the same way.” Kargar reiterates this point by drawing parallels between issues in Afghan communities across the imagined East-West divide: “in some cities families have started letting their daughters and sons go abroad for higher education, taking up the scholarships being offered to young Afghans by western countries. Yet here in London I have met Afghan parents who strongly oppose the idea of their sons or daughters even living in student halls of residence, as the family’s reputation could be damaged.”

Those Afghans raised in the West often experience the effects of being Afghan without knowing why. We see the correlations but are cut off from the causes; we carry the fear without seeing the war, and the shame without the nang. Yet, there are so few resources to study Afghan womanhood. As a rare instance of written documentation within an otherwise oral tradition, this anthology is especially important for studies in the humanities, particularly in Afghan women’s studies, sociology, and history.

There are so few resources to study Afghan womanhood.

Muzgan’s story was my favorite of them all. Huddled in a shelter as bombs fell over her family and their neighbors, the precocious little girl maintained her carefree spirit through song and dance, and she spread it to the other children huddled with her. Muzghan’s mother tells her to stop playing music and adopt a somber mood appropriate for the situation: “Muzgan, you shameless girl! Can’t you see we’re in terrible trouble? There might be no food for us tomorrow. Any of us could die. You should be teaching the girls to pray for the war to end.”

I want to die when I’m dancing. I want to die happy.

Muzgan boldly stands up to her mother, something many of us, even in the “empowered” West, never manage to do: “I don’t want to die feeling sad. Who knows? We might all die tonight, but I want to die when I’m dancing. I want to die happy. When you die, Mother, you’ll die worrying.”

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★

DEAR ZARI: THE SECRET LIVES OF THE WOMEN OF AFGHANISTAN By Zarghuna Kargar | 272 pp. | Sourcebooks| $15.99